Photography as a whole is a cumulation of many ideas and contributors.

Eric Renner explains the origins of pinhole photography beautifully in his comprehensive book ‘Pinhole Photography, From Historic Technique to Digital Application’. From the earliest recorded descriptions of pinhole optics by Mo Ti in China (400 BC) right through to Joseph Nicéphore Niépce’s first ever ‘heliograph’ and work by more current pinhole photographers. Solar photography or heliography images from artists such as Dominique Stroobant and Hiroshi Yamazaki precede our digital era. But with the advent of modern scanning technology and the internet, Diego Lopez Calvin, Slamowir Decyk and Pawel Kula initiated project ‘Solaris’ in 2000 and dubbed the practice ‘solargraphy’ . The project aimed to capture half-yearly records of the sky between solstices in different parts of the world. The cameras used in the Solaris project were ordinary pinholes with light-sensitive paper inside and the project was open to all those interested. Konrad Smolenski, Wojtek Hoffman, Przemek Jesionek and Ramon Chomon were also experimenting with a similar technique. Tarja Trygg set up the Global Project of Solargraphy and carried on collecting images from all around the world.

As a result, the process of using pinhole cameras for heliography or solargraphy became increasingly popular. In our technologically driven era, this wondrous simplicity is captivating the imagination of many inquisitive minds.

Dominique Stroobant

Dominique Stroobant, a Belgian-born stone sculptor and pinhole photographer was one of the true pioneers in using solar activity to make time sequencing cameras in the late 1970’s.

‘In addition to stone sculpture, Stroobant employed the nearly forgotten technique of pinhole photography since 1977. While working on his stone sundials, he asked himself this simple yet surprising question: “What does a sundial see?” For Stroobant, this was the beginning of an exciting journey into the world of the pinhole camera. For him, it is an artist’s duty to probe the unknown and the possibility of failure is an essential component. In his work, Stroobant often deliberately assumes the position of a beginner who is not satisfied with established methods, and instead seeks primary experience from the sheer joy of experimentation. In the context of a new appreciation for slowness, we must mention Stroobant’s trials in which he prolonged the exposure time from one day to the unbelievable interval of six months. The result was a series of photographs that derive their allure from the path of the sun. They are playful experiments in producing previously unseen images, which expand the viewer’s perceptual horizons. The slow process of etching the image into the material is the connection between pinhole photography and sculpting. The light and the tool both leave their marks. In addition, both techniques require methodical planning according to scientific criteria in order to achieve relevant, verifiable and in principle also repeatable results’.

Shortened version of Dirk Pörschmann’s essay, written on the occasion of the Dominique Stroobant’s monograph published by Axel and May Vervoordt Foundation in association with Axel Vervoordt Gallery and AsaMER, an imprint of MER. Paper Kunsthalle, October 2015.

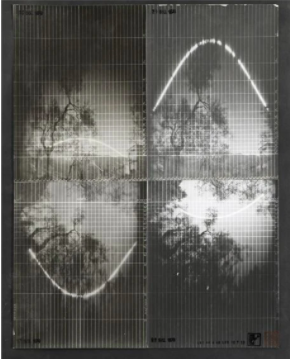

Renner Eric, Pinhole Photography, From Historic Technique to Digital Application, Focal Press, Images Pages 88-89

Renner: “During the 1980’s, Dominique Stroobant continued his work of photographing the sun. He made many cameras that could remain outside for an extended period of time, even as long as six months. For many projects he used multiple cameras, each one which was aimed at different angles-from horizon to zenith in the sky. What is amazing is that Stroobant can still achieve a correctly exposed view of the landscape while photographing the sun for as long as six months. Stroobant used very slow litho film to make these images and he layered many sheets of film in the cameras. After taking each camera back into the darkroom, he selected the piece of litho film that seemed to be exposed correctly for both landscape and the solar image”.

Stroobant: “I got trapped by pinhole photography, once I discovered how obvious and pleasant it was to realise everything from the start. My tools could not be ready made. Why try to conceive anything more sophisticated than the cameras presently in use: there is more enjoyment the other way. Since Niepce in photography nothing else has been done but to reduce space and time to smaller fragments at each step. Once I showed people what I could realise with these clumsy, heavy but still handsome devices of mine, they thought it was sorcery. However, I believe, all they are accustomed to use is real sorcery! Just try and dismantle any camera of today.”

Renner Eric, Pinhole Photography, From Historic Technique to Digital Application, Focal Press, Page 86

Hiroshi Yamazaki

Heliography (1974) is a body of art representing over ten years of work. Fixing his camera over a featureless coastline, Yamazaki captures the slow arc of the sun with super long exposures. His powerful compositions capture bands of sunlight and their fierce reflection on the water below. The Photographic Society of Japan awarded him first prize in 1983 for a series of time-exposed photographs of the sun over the sea. One of his interests is pursuing the role light plays in photography, rather than just reproducing scenic beauty.

Links: